“The world gets softer when you treat each person as a whole story, not a passing moment, and you let their humanity slow you down.”

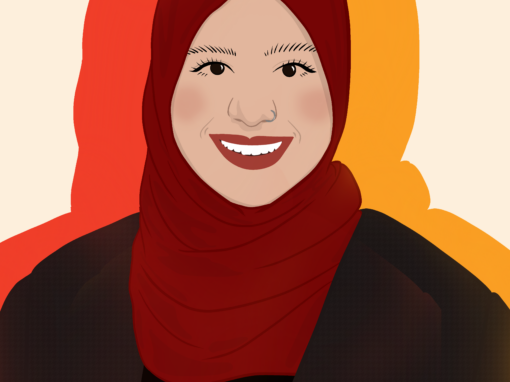

Ameen Alizada

TOP 30 UNDER 30 HONOUREE | 2026

About

PROFILE SNAPSHOT

AGE: 23

PRONOUNS: He/Him

HOMETOWN: Calgary, Alberta, Canada

CURRENT RESIDENCE: Calgary, Alberta, Canada

ORGANIZATIONS:

- Cleats4Kids Foundation

- Calgary Stroke Program

- Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB)

- Calgary Police Service Victim Assistance Program (VAST)

- Alberta Sport and Recreation Association for the Blind (ASRAB)

GLOBAL IMPACT FOCUS (SDGs)

I am most passionate about:

What specific issue(s) are you working to address, and what motivates you to do so?

The work I care about sits across sport and healthcare, where barriers can quietly determine who gets a fair chance to take part. When children cannot access sport, they lose a place to belong, a way to build confidence, and a path to better health. I care about this because sport shaped my own sense of community growing up, and because I now see the same barriers in healthcare. For many children, the barrier is not motivation, but it is the gap between wanting to participate and having a fair chance to do so. Program fees, transportation, and equipment costs add up fast. Families new to Canada often navigate unfamiliar systems, limited time, and limited networks. Some kids carry the stress of displacement or trauma, and sport can be one of the few places where they can feel safe and steady, but only if the environment is welcoming. Other children live with disability or chronic health challenges in a world that was not designed for them. They may face a lack of adapted programming, coaches who are not trained to include them, and settings that unintentionally exclude them.

My main work is through the Cleats4Kids Foundation (cleats4kids.ca), the nonprofit I co-founded to reduce barriers to sport for marginalized children. We focus on low-income families, refugee and newcomer youth, and children living with disabilities. We build partnerships with schools, settlement agencies, and local sport organizations, then deliver free and inclusive soccer programming and community events. One initiative I am especially proud of is our visually impaired soccer programming. We worked with community partners to design sessions that make the game accessible in a practical way. We used balls with bells so athletes can track the ball by sound, and we structure drills around clear communication and predictable spacing so players can move with confidence. For many families, it is one of the first sporting spaces where their child can participate fully and feel like they belong. We also run events that build connection beyond sport. At our river cleanup, we invited youth soccer teams from across the city to show up together and care for a shared space. Players who would usually compete worked side by side with parents, coaches, and volunteers. It gave youth a simple way to contribute to their community and see themselves as stewards of the environment.

These principles also shape how I think about healthcare. I have learned that outcomes depend on more than the quality of the care itself. They also depend on whether people can access it, understand it, and feel comfortable engaging with it. I want to keep working at the intersection of health and participation by supporting approaches that fit into real lives and reduce barriers that are often overlooked.

What are the ways in which you curate connection?

I attempt to curate connection by making space for other voices and shaping the work so people can see themselves in it. During my work in the community, I try to keep communication clear, adjust my approach to the group I am working with, and follow through so trust can build over time. Most of what I do depends on working with families, youth, educators, coaches, community organizations, and volunteers. I have learned that people stay engaged when they feel heard and when their input shows up in the final plan.

In academia, I see connection as asking questions that make space for people who are often left out. As I continue to get involved in research, I want to help bring underrepresented groups into healthcare research and discussions, so the evidence we produce reflects more of the people it is meant to serve. Taken together, connection comes from listening first, sharing decision making, and shaping both community work and research around the people they are meant to serve.

What role will connection play in your future work?

Connection will most certainly guide my future work because it shapes whether people feel included, understood, and willing to take part. Through Cleats4Kids, the goal is not only to run programs. It is to help kids and families feel that they belong in the spaces around them. When a child feels welcome on a team, they are more likely to keep showing up. When parents trust the people running a program, they are more likely to ask questions, share concerns, and stay involved. Over time, that sense of belonging becomes a kind of stability that many families do not have when they are new to a city or facing barriers.

As a medical trainee, connection matters for similar reasons. People thrive when they feel heard, understood, and respected. That often comes down to listening well, explaining things clearly, and taking seriously the story someone brings into the room. We also live in a time where technology connects us quickly, but many people still feel alone. As AI tools become more common and advanced, it will be even more important to stay grounded in real relationships and in the lived experiences of the people around us.

More Top 30s from 2025