“As you navigate your own path, it is okay to feel confused and to explore, as you can only begin to understand your boundaries, your possibilities, and what you carry when you step into new spaces and learn alongside others.”

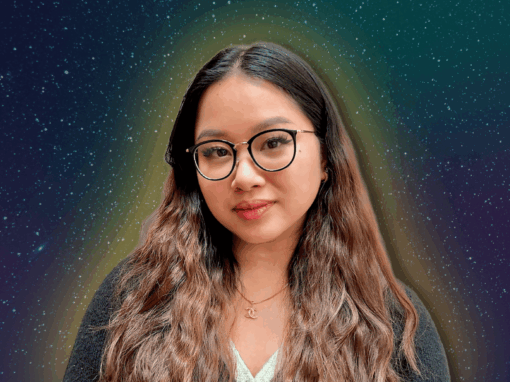

Rochelle

Mission Deloria

TOP 30 UNDER 30 HONOUREE | 2026

About

PROFILE SNAPSHOT

AGE: 26

PRONOUNS: She/Her

HOMETOWN: Calgary, Alberta, Canada

CURRENT RESIDENCE: Calgary, Alberta Canada

ORGANIZATIONS:

- Filipinos Rising (FRIENDS)

- Faculty of Social Work, University of Calgary

- ActionDignity

GLOBAL IMPACT FOCUS (SDGs)

I am most passionate about:

What specific issue(s) are you working to address, and what motivates you to do so?

As I reflect, I came to this work through my family and through community. Growing up as a second generation Filipina Canadian and an older sister shaped how I understand care, responsibility, and advocacy, particularly within racialized and immigrant families where support is often assumed, shared quietly, and rarely acknowledged. Even before I had the name or language for systems or policy, I learned what it meant to navigate responsibility across systems that included, family, school, and community, and to hold roles that were necessary but largely invisible.

When entering community, or meeting others, I often introduce myself first as a second-generation Filipina Canadian, an older sister, a student, and a community member before naming my professional roles. This is intentional, as my work is not separate from my lived experience. When my younger sibling entered the mental health system, I stepped into a caregiving role that shaped how I understand care, advocacy, and responsibility. Moving through clinical spaces alongside my family revealed how siblings and caregivers are often relied upon to hold families together while being excluded from decision making, particularly in immigrant households. These experiences continue to guide how I move through research practice, and community, and further inform my understanding of how responsibility and resilience become normalized within systems shaped by migration, racism, and uneven access to care.

Beyond research, I work across community and clinical settings to address how gender, culture, and power intersect in mental health and family systems. A central part of this work has involved creating spaces where racialized youth and mental health practitioners can learn alongside one another. Through anti-racist mental health education initiatives, I have helped convene youth, clinicians, and facilitators to reflect on how racism, gender, and trauma shape therapeutic relationships, and how care can be practiced more responsively and accountably. These spaces are intentionally relational, grounded in listening rather than expertise, and designed so that youth experiences inform how clinicians understand harm, safety, and healing.

Alongside this, I have facilitated community conversations on family violence and intergenerational conflict, and provided gender-affirming care to trans and gender-diverse clients and families. Across these spaces, I understand gender as one part of a broader web of identity shaped by power, culture, and systemic inequality. What motivates me is a belief that care must be relational, culturally grounded, and accountable to the people most impacted, and that lasting change happens when those most affected are not only heard, but help shape how care is imagined and delivered.

What are the ways in which you curate connection?

In community, I move to curate connection by working alongside people rather than positioning myself as an outside expert. Much of my work involves creating spaces where individuals who are often separated by systems can meet one another with care, and shared responsibility. These spaces bring together youth, families, clinicians, researchers, and community members, and are grounded in listening rather than performance.

In community settings, I facilitate conversations that allow people to speak openly about care, safety, grief, and belonging, particularly during moments of collective stress. These gatherings are not about extracting stories or producing outcomes, but about building trust and shared understanding. In my research and evaluation work, connection is built through participatory approaches that allow lived experience to shape interpretation, direction, and meaning.

I also curate connection by creating reflective spaces where power can be named and examined. This includes peer spaces where students unpack power dynamics in education and shared learning spaces where clinicians and community members reflect together on practice and systems. Across this work, I try to remain attentive to when my voice needs to step forward and when it needs to step back.

One moment that deeply shaped my approach was being invited back as a speaker for youth I had previously worked alongside, not as an expert, but as someone whose path had been shaped by them. That experience reinforced for me that connection is reciprocal and that meaningful collaboration requires humility, patience and a willingness to be changed by the people you work with!

What role will connection play in your future work?

Connection will remain central to my future work as a social worker, researcher, and community advocate, not as a guiding concept but as a practical orientation. I have learned that work grounded in relationships requires more time, more listening, and more accountability, especially when working within systems that are not designed with racialized and immigrant families in mind.

In my future path in social work, this means paying close attention to family relationships, cultural context, and the ways care is distributed across siblings and generations. This also means recognizing that healing is influenced by community connection through areas such as housing, work, migration histories, and caregiving responsibilities, not just individual responses. In research, connection shapes how I ask questions, how I interpret stories, and how I think about where findings belong once the work is done. In advocacy work it means taking direction from lived experience, even when that complicates timelines or institutional expectations.

I do not see connection as something that simplifies change, but rather as a tool to introduce tension, disagreement, and responsibility while keeping the work grounded. When people remain connected to decisions that affect their lives, change may move more slowly but it is more likely to be responsive and sustained!

More Top 30s from 2026